One of the first misconceptions we have to get out of the

way is that corn is actually corn. The word corn doesn’t literally refer to the

stuff on the cob we eat in the summer and the stuff we pop on a

cold afternoon. What we call corn is much more accurately called maize.

The word "corn" comes from an old german/french word. In most

uses before the 1600’s, corn meant the major crop for one particular area or

region. In England, corn meant wheat; in Scotland or Ireland, it most likely

means oats. There is even mention of corn in the King James Bible. This was

translated several times and hundreds of years before maize arrived in Europe.

The “corn” of the Bible most likely means the wheat and barley that were grown

in the Middle East at the time.

When Columbus took maize (Zea mays) across the Atlantic to Europe, he might have referred to

it as the chief crop of the Indians; therefore, it was Indian corn. After a

while, domesticated maize became so ubiquitous that the word “Indian” was

dropped, and all maize became corn – like all facial tissue becoming Kleenex.

The history of maize is, well, a-maizing. The corn we know

today is the most domesticated of all crops. It can’t survive on its own; it

has to be managed by man. Rice and wheat have naturally wild versions of

themselves that still grow in nature, but there is no wild corn, it is

purely man-made.

A recent article from Florida State shows that corn was being bred and harvested

as early as 5300 BCE.

The early plants were quite variable, growing from 2 to 20

feet tall. The ears, when they developed, were small and had only eight rows of

kernels. More breeding took place, especially when the plants were brought

north. At that time, ears grew near the top of the plant, and the growing

season in the north was too short to allow full development.

Maize is a grass, so it has the nodes and internodal growth as we discussed a few months ago. Corn grows about 1 node unit for each full moon;

the Indians needed a corn that would mature in just three moon cycles. So they planted

kernels from stalks that had the lowest ears, thereby selecting for plants they

could harvest before it got too cold. Their selection was for size and

production, but colors came along for the ride.

There are many color genes possible in maize. A new version,

called glass gem corn, shows just how many colors are possible (see picture). Indian corn, as we define it now,

can be found in most of these colors; sometimes ears are all one color,

sometimes they are combinations of colors. It all depends on who is growing

nearby, but we need to know a little more about corn in general to explain

this.

Maize is a food grain,

meaning that has small fruits with hard seeds, with or without the hulls or

fruit layers attached. More specifically, maize is a cereal grain, because it comes from a grass. Wheat is a grass, so

is barley, rice, and oats. Basically, these are the grains your morning cereal

is made from, so which came first, the breakfast “cereal” or the “cereal”

grain? The answer is out there.

And by the way - yes, grains are types of fruits. The fruit

is more precisely called a caryopsis (karyon means seed); a small fruit and

seed from a single ovary, which doesn’t split open when mature (indehiscent). One of the

characteristics of most grains is that the pericarp (the fruit) is fused to the

seed coat, so it is difficult to talk of the fruit without including the seed.

It's the hull that shows the color of a kernel of maize. You

can pop blue, red, or purple corn, but the popcorn will still be whitish

yellow. The color genes are present in all the cells of a kernel, but they are only expressed

in the epidermis or hull; this will be important in a minute or two.

So how can Indian corn have kernels of different colors? The

same way that you and your siblings look different. Each kernel is a different

seed, so each is a different potential plant. The male flowers of the corn

tassel send out grains of pollen to pollinate the female flowers. Each pollen

grain has a sperm cell, and each has undergone the same process of mitosis and

meiosis as human sperm – there is genetic variation there.

The female flowers are the silks on the ear of

corn. Each silk is connected to a different ovary (potential kernel). Again,

each egg is a different version of the maternal plant’s genome. Different silks

could be pollinated by different male plant pollens floating around in the air

– nothing says that all the kernels must have the same dad.

So, it isn’t to difficult to see that different kernels

could be different colors, either from random assortment and mendelian

genetics, or from different pollens meeting different eggs. The reason we eat

yellow corn or white corn or yellow/white corn is because the color genes have

been selected for by breeding, and the pollination process is highly controlled.

This is not the case with Indian corn.

So that’s the story for corn color – or is there more? Look

closely at Indian corn above; some kernels have streaks or spots of color. How does

that happen?! This is completely different from having kernels of different

color, and relates to one of the great exceptions in DNA biology.

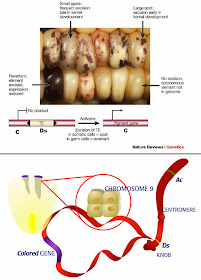

Barbara McClintock found that by observing the chromosomes

of maize very carefully, specifically chromosome nine, and by looking at the

resulting kernels from selective breedings, she could match changes in the

chromosome to changes in color streaks and spotting.

She noticed changes in the length of the arm in some cells,

and related this to the movement of genes along the chromosome. To this point,

all scientists believed that genes stayed in the same place on a chromosome

forever. McClintock saw genes jumping from one place to another. She called

them transposons.

When Ds was located inside C, no color was produced, but

when it was not, the daughter cells could produce color. A kernel has many

cells that divide and divide, so some progeny could switch back and forth and

produce cells on the hull that may or may not be able to produce the color

protein (see picture). If the move to disrupt C occurred early, more

daughters would be produced and more of the surface would lack color. If it was

late, the spot would be smaller (see bottom image to left).

This idea of jumping genes was revolutionary …. and not well

accepted at first. Even though Barbara’s science was impeccable, others just

weren’t as good at spying the small changes in the chromosome. It took a while

for the laboratory techniques to catch up to Barb’s eyes – then they gave her

the Nobel Prize.

From our new knowledge of transposons have come many

discoveries – some not so savory. Some infectious agents, both bacterial and

eukaryotic, use jumping genes to escape our immune system. Neisseria gonorrhea was one of the first shown to do this. Our

immune system, given time, will find bacteria that have taken up residence

inside us; in gonorrhea's case, through sexual transmission.

N. gonorrhea has

found that if it can change its costume, our immune system must start over

looking for it. The proteins it has on its surface are what our immune cells

recognize, we call them antigens. Gonorrhea organisms can go through antigen variation; they have many

surface antigen genes, and can switch them out if they are detected.

In the case of Pneumocystis,

a 2009 study showed that there are over 73 major surface glycoprotein (MSG)

genes that can be switched in and out. They differ by an average of 19%, so the

protein sequence of each is markedly different. Even though we don’t know the

function of the MSG, it would appear that it is designed to increase the

variation of the organism, probably to avoid an immune response.

Still have that warm and fuzzy feeling about Indian corn as

a representative of Thanksgiving?

Next week, we start to look at the last of the four biomolecules - lipids. Can you believe some people can't carry any fat on their body, no matter how much they eat?

It just so happens that Barbara McClintock and her corn made up a portion of a recent exhibition at the Grolier Club in NYC, entitled, "Extraordinary Women of Science and Medicine: Four Centuries of Achievement." The exhibit included one of Barbara's ears of corn and some of her breeding materials. The catalogue is available from Oak Knoll Books. Thanks to Karen Reeds, independent curator and museum consultant for the heads up.

Next week, we start to look at the last of the four biomolecules - lipids. Can you believe some people can't carry any fat on their body, no matter how much they eat?

It just so happens that Barbara McClintock and her corn made up a portion of a recent exhibition at the Grolier Club in NYC, entitled, "Extraordinary Women of Science and Medicine: Four Centuries of Achievement." The exhibit included one of Barbara's ears of corn and some of her breeding materials. The catalogue is available from Oak Knoll Books. Thanks to Karen Reeds, independent curator and museum consultant for the heads up.

For

more information or classroom activities, see:

History

of maize –

Transposons

–

Antigenic

variation -