Biology concepts – semiochemicals, hematophagy, proboscis,

thermosensing, TRPA1

thermosensing. It seems

that some people are bitten by mosquitoes if they peak out the front door,

while other people can sit outside next to tall grass or ponds for hours with

suffering a single bite. Unfortunately, I happen to be in the former category.

How do mosquitoes

find some people and not others? Are some people just tastier than others?

First let’s get some common misconceptions and basic

information out of the way. Do mosquitoes bite you (or any other animal)? No,

they have no teeth, so they don’t bite in the traditional sense. What they do

have is an elongated set of mouthparts called a proboscis. The sheath on the outside retracts as the longer parts

inside pierce the skin like a hypodermic needle. Only this is a flexible

hypodermic needle, small enough to go around individual cells and look for a

small vein or venule.

Take a look at these videos taken from a 2012 PLoS One study of a mosquito biting a mouse. The squarish objects are skin cells, and

the red streaks are blood vessels. The second video in the sequence shows what

happens when the proboscis finds a vessel and starts to suck out the blood.

Makes you respect the mosquito a bit more – these are some determined females.

Of course it’s only the females that feed on blood. This

suggests that feeding on blood is related to having babies. And it is – just

not in a “gotta get the baby some food” sort of way. Most mosquito species

require a blood meal in order to develop viable eggs. Females get energy from

drinking nectar (full of carbohydrates), but they need protein to produce yolk for

the eggs. They get the protein from feeding on blood. If the female doesn’t

feed on blood, the eggs will be produced, but they won’t be able to hatch and

become larva.

But here is one of our exceptions – some mosquitoes have gotten around the need for blood meals. All 92 species of mosquito in the genus Toxorhynchites (elephant mosquito) don’t need to feed on blood. Instead, their larvae feed on the larva of other mosquitoes, and the gather the proteins they need to lay viable eggs from their larval meals. They store the amino acids in their larval and pupal bodies, until they become adults and need them to lay eggs of their own.

This suggests that the elephant mosquitoes could be used to combat disease spreading mosquitoes, like the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that spread dengue fever, yellow fever and the current disease of interest, chikungunya fever. And the elephant mosquito has been used as a natural biocontrol agent. What's weird is that A. aegypti females actually help the situation.

A. aegypti, and many other mosquitoes that lay eggs in water, have larvae that eat bacteria. So they want to lay eggs where there are a lot of bacteria. Well, the eating of larvae by Toxorhynchites species leaves lots of little pieces of mosquito larva in the water, and this provides bacteria with a lot of food. A June 2014 study showed that A. aegypti females actually prefer to lay eggs in water that contain predators for their larva, because it increases the bacterial numbers so much. Thos that survive have lots of bacteria to feed on. It’s a calculated behavior – risk being eaten or risk starving.

So some mosquitoes will go a long way and risk death in

order to get a good meal for their potential offspring. They’re looking for

mammals usually, but even here there are exceptions. Some mosquito species,

like Culiseta melanura, feed almost exclusively on bird blood – they

say it tastes like chicken.

But

just because they feed mostly from birds doesn’t mean they aren’t important

disease transmission. They are – for horses. Eastern equine encephalitis virus

is passed from bird to bird by C. melanura, so the birds, especially cardinals, are a

reservoir of virus. Then, when another species of mosquito that is less

particular about its host species bite a bird then bites a horse or person, the

disease can be spread. There are even cases where a C. melanura will occasionally feed on a human and spread the disease directly.

With this

background, we still need to answer our question of the day – how do mosquitoes

find a blood meal. Believe it or not, your socks help answer the question. For

many years it was assumed that mosquitoes followed the heat of warm-blooded

animals in order to find a meal, but this was an assumption that was not tested

rigorously.

Then it was

discovered that carbon dioxide (CO2) is a strong cue for mosquitoes

seeking sustenance. CO2 means respiration, and respiration possibly

means mammals. The mosquitoes have taste receptors in their antennae and mouths

that will sense changes in CO2 and they will follow the path of more

carbon dioxide right to your nose and mouth (see this post).

Large people

and pregnant women tend to exhale more CO2, so they will be more

attractive to mosquitoes. But there are large individuals who never get

bothered by mosquitoes. Maybe there’s more to it.

Semiochemicals are part of the answer. Semio- comes from

the Greek meaning signal, like in semaphore flags. So semiochemicals are

molecules emitted by organisms for communication. Pheromones are the most

famous of the semiochemicals – and we know that these are used in many animals,

from helping to guide ants to follow the path of their predecessors, to

influencing mate choices in many animals.

Semiochemicals

might be attractants or repellants. In some cases, they can be both. Take human

body odor – it contains dozens of semiochemicals, people find body odor repulsive,

but mosquitoes enjoy it like the smell of fresh apple pie. Of course, body odor

is only offensive nowadays; before the advent of deodorant, daily or three

times daily baths and showers, perfume, aftershave, and of course Axe products

– everybody smelled like that guy that lives under the bridge.

Bacteria

feed on the sweat, sugars and proteins that mammals exude, and they give even

more semiochemicals. This can make you more or less attractive to mosquitoes.

In general, people with many types of bacteria on their skin are less attractive,

while those with mostly a few attractive species will get bitten more often.

Having a high number of bacteria is a turn off too, probably because that would

expose the mosquitoes to more possible pathogens as well. Is it possible to be

so disgustingly colonized that even mosquitoes won’t land on you?

Mosquitoes are

attracted to several different semiochemicals, including octenol, CO2,

and nonanal. On mosquito antennae, especially the female antennae, there are

receptors in the sensilla (see this post) for at least 27 different chemicals

in human sweat.

Studies have

shown that old socks are a good experimental attractant for mosquitoes. Instead

of using an arm or other body part, scientists will compare the attractive

ability of someone’s old sweat socks to individual chemicals or mixtures of

chemicals. Of course, whose socks you use matters as well. Some people are

classified as high attractors (HA) and some as low attractors (LA), so studies

often include comparisons of chemicals or mixtures to both HA and LA socks.

But there are

other considerations as well. People with blood type O secrete different semiochemicals

and are more attractive to many species of mosquitoes. Go ahead, try to change

your blood type so you’re less attractive to mosquitoes.

Different

species may aim for different body parts. Some seem to prefer feet and ankles,

but this may be because they are closer to the ground. If convection currents

created by the body heat rising suck the mosquitoes in from below, then it is

really the fact that they are following their noses and not going after feet

particularly. A small 1998 study showed that mosquitoes that went after feet

and ankles preferentially did not do so when the volunteers lied on their backs

and raised their feet high in to the air. But, what we have stumbled across in

this discussion is body heat.

But what was old is new again…. Scientists are again looking at heat as an attractant for mosquitoes. As compared to HA or LA socks, heat isn’t a strong attractor, but warm socks attract more mosquitoes than cold socks. On the other hand, a 2010 study says that heat and moisture is a greater attractor than heat alone, so it would seem that people working outside in the heat would be the perfect attractors for mosquitoes.

Since heat does

seem to be an attractor, it would follow that female mosquitoes would have a

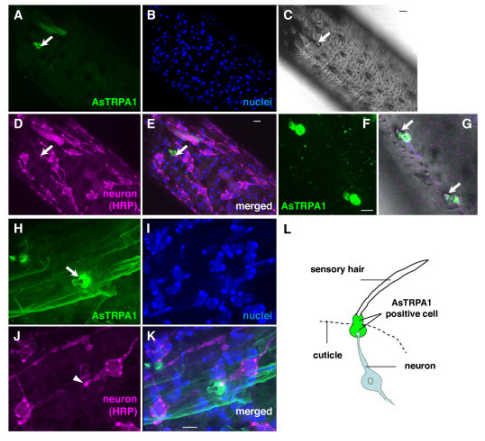

receptor for heat. Voila, a new study shows that mosquitoes have sensilla on

their antennae and palps that house TRPA1 ion channels. A 2011 study even

showed that one malaria-carrying mosquito has TRPA1 receptors on its proboscis.

We have talked before about how many mammals use this receptor to sense noxious

cold as well as chemicals that cause irritation or pain.

But in birds, reptiles and insects, TRPA1 is a heat sensor. The 2009 study

showed that the TRPA1 were expressed on the female antennae only. But that

isn’t to say that only female mosquitoes have TRPA1. A 2013 study indicates

that A. gambiae mosquito larvae have functioning TRPA1 so that they can sense water

temperature and stay in the most comfortable water.

So mosquitoes

(most female mosquitoes) are finding suitable hosts for blood meals by using

their senses of taste, smell, sight, and infrared detection. There are other

vampire insects as well, ticks, bedbugs, etc. I wonder if they are using heat

sensing too. These have yet to be reported on.

Next week, a

related question – just how and why do mosquito repellants work?

No comments:

Post a Comment